Whether sweet or tangy, sauced or dry, pulled, sliced, or on the bone, everyone loves barbecue. Barbecue is a product of meat, smoke, time — and history. It is an institution that defines us as a nation. Barbecue is a quintessential piece of American culture, with deep roots and a complex history. The history of barbecue is the history of America.

Tracing the exact origins of barbecue is a messy business, one that’s impossible to discuss without pissing people off. It is omnipresent and elusive in the history of mankind. Is barbecue simply a cooking method like grilling or smoking, or is it something more? Barbecue is hard to define. Even the word has variations. Is it “barbecue” or “barbeque” or “bbq?”

Many of these answers vary depending on whom you talk to. A barbecue purist might peer under the hood of my Yankee smoker and say, “That’s not barbecue.” Who’s to say they’re wrong? In reality, the story of barbecue is a complicated web of competing narratives and accounts. Although many claim ownership and the right to define the genre, barbecue’s story does not belong to a single person, group, or historical event.

Barbecue, like America, is messy history.

Broadly defined, “barbecue” means to cook over hot coals. In that case, the history of barbecue is the history of human evolution. Hominids have been cooking this way for hundreds of thousands of years. Barbecue was a significant factor in our evolution — from tree-dwelling prey animals to bipedal hunter-gatherers. As our ancestors evolved into modern humans and dispersed out of Africa, unique cultures formed, as did their foodways. Tribes, empires, and civilizations rose and fell, yet the cross-cultural practice of cooking meat over hot coals persisted.

To this day, we can see this broad definition of barbecue in many forms worldwide: from Japanese yakitori and Korean gogigui to Indian tandoori and Jamaican jerk. It’s difficult to pinpoint precisely when, where, or how barbecue became barbecue without favoring one aspect of the story or ignoring another.

Perhaps the best place to start is with the word itself. Several theories for the term’s origins range from the plausible to the outlandish, but experts mostly agree that “barbecue” comes from the word “barbacoa.” Barbacoa originated with the Indigenous people of the Caribbean and refers to a raised wooden structure used for slow cooking over coals.

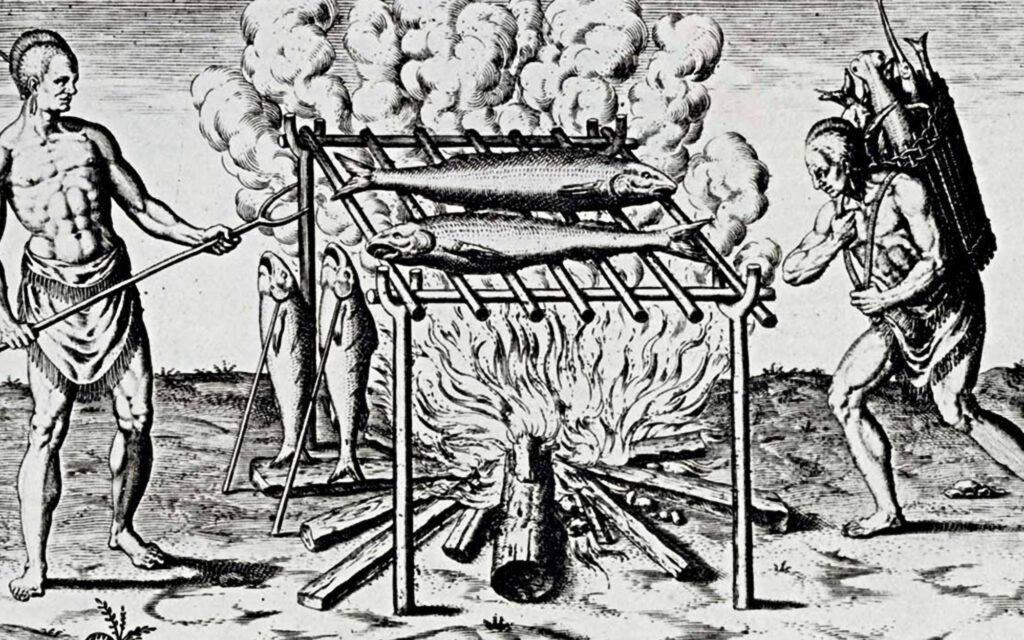

The Taino people and other Native Arawak groups used this method to cook and preserve fish, meat, tubers, and other foods. While it’s hard to say exactly when or where Indigenous people began using this timeless technique, European contact catalyzed its place in the psyche of the wider world.

When Christopher Columbus landed in the Bahamas, he encountered the Taino people and their barbacoa. A few decades later, as the Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto reached the Mississippi River, he met with a group of Chickasaw who cooked one of his pigs over barbacoa. As the Spanish pillaged and enslaved their way through the Indigenous population, they became fond of the barbacoa method, adapting it to European tastes and ingredients.

Pork was a staple of the Spanish colonial diet, and barbacoa became a favorite way to cook it. Pigs are hardy animals that provide a lot of meat, reproduce rapidly, and are relatively low-maintenance to raise, making them preferable over other livestock.

The porcine population quickly skyrocketed and spread geographically from the original 13 pigs that de Soto brought to the Americas. By AD 1607, the Spanish were trading pigs to the English settlements in Jamestown, Virginia. By 1652, the pig population was so out of control on Manhattan island in New York that the Dutch settlers there built a massive protective wall to keep feral pigs, hostile natives, and the encroaching British out.

This area, which came to be known as “Wall Street,” was the first government-sanctioned slave market in New York City. Barbacoa cooking spread throughout the colonies through the trade of both pigs and slaves as well as natural, cultural diffusion.

Around the cooking fire, Native American, Caribbean, and African foodways intermingled with the customs of the European colonists, forming the basis of many new uniquely American culinary traditions.

By the time of the American Revolution, the Spanish were on their way out of North America, but their pigs and influence on barbacoa were here to stay. Barbacoa became barbecue, and the craft was passed down through generations of cooks, mostly slaves who did the lion’s share of food preparation at the time.

Because barbecue was a time-consuming process that required skill, it wasn’t a meal cooked every day. It began to take on cultural significance as something done on special occasions and in celebration. Barbecues were often held alongside weddings, parties, and other social gatherings.

Eventually, church functions, festivals, and political rallies began to feature barbecue as an inexpensive way to draw and feed many people. Barbecue trenches dug into the ground became necessary to cook the whole hogs needed to feed a crowd. These barbecue pits and whole-hog cooking became well established in places like the Carolinas. Barbecue became not only central to the southern experience but an integral piece of the broader American culture.

Although slavery technically ended at the close of the American Civil War, Jim Crow laws and virulent racism remained widespread. Without money or options, former slaves and their families found employment using the skill sets they already had, such as cooking barbecue.

While many found themselves trapped in the institutionalized poverty of the southern sharecropping economy, barbecue became a way out for some. Black-owned barbecue businesses often started as pop-up shops or street vendors that later expanded into brick-and-mortar establishments. Some became very successful in bringing wealth and employment to their families and communities.

While barbecue often found itself at the center of racial division in America, it also served as an agent of diplomacy. White and Black Americans were working at each other’s restaurants and clandestinely eating each other’s barbecue, even though the country was still segregated by law. When Katzenbach v. McClung made its way to the Supreme Court, it signified a fundamental turning point in barbecue’s troubled history.

The Court upheld Congress’s decision forbidding racial discrimination in restaurants. This landmark case finally brought equality and dignity to barbecue. We could be proud of barbecue as Americans. Whether it was a culinary kumbaya moment, the pursuit of the almighty dollar, or a combination of both, as time went on, the distinction between white and Black barbecue gave way to American barbecue, something we all had in common.

Barbecue, in one form or another, found a place at America’s table. Over time, particular cuts of meat and styles of sauce have come to characterize the regional identities we know and love:

In South Carolina, whole-hog barbecue continued to be associated with a celebration in the social context of southern church culture. Mustard-based sauces became characteristic of the region due to ethnic German and French influence.

In North Carolina, English ancestry shaped the style of barbecue to a more vinegar-based sauce.

In Memphis, Tennessee, the river trade led to tomato-based sauces sweetened with imported molasses.

When Henry Perry brought his knowledge of Tennessee barbecue to Missouri and started including beef and other proteins beyond the traditional pork, Kansas City style was born.

In the Midwest, in places like St. Louis and Cincinnati, the proximity to farms and processing centers meant cheap cuts were readily available in many of these “barbeque-belt” states.

In Texas, which had a whole lot of cattle and was a central part of the economy, barbecue became predominantly beef-focused.

In Alabama, a white mayonnaise and vinegar-based sauce on chicken and pork established a unique regional style.

In Mississippi, the many styles of the “barbeque-belt” converged along the meandering Mississippi River and its nearby patchwork of highways, taking root at roadside pit stops and in the juke joint culture that brought blues music to the world. Barbecue, in all its forms, became integral to Mississippi identity, and today, the state holds more titles in barbecue competitions than just about anywhere else.

In Chicago, the influence of Eastern European immigrants led to a barbecue tradition of boiled and smoked ribs and sausage.

South of the border in Mexico and Central America, barbacoa cooking took its own path, branching into entirely new styles, heavily influenced by the Indigenous and Spanish foodways that had birthed it.

These and other barbecue styles around the world trace their story to a common lineage. From the cooking fires of our hominid ancestors to the Indigenous tradition of barbacoa usurped by the Spanish to the pitmasters of the American south, the history of barbecue covers the range of the human experience — the good, the bad, and the ugly.

The interplay of these forces is why barbecue is a piece of culture—and not just a cooking method or a type of sauce. It is as much a piece of history as it is a delicious smoky meal. While America’s love of barbecue transcends many of the bullshit ways we try to divide ourselves, it’s essential to understand its complicated, often tragic history without letting any particular narrative overshadow the whole.

If you’re an American, barbecue history is something to be both proud and ashamed of, to celebrate and contemplate. Time and good food can heal many wounds, and luckily for us, time, along with meat and smoke, is the main ingredient in barbecue.

Click HERE to read the full article by Cosmo Genova on freerangeamerican.us.